This is Part 1 of the Voluntary Discomfort Series. Part 2 is about my own experience and takeaways doing three days of voluntary discomfort.

*Check out Part 2 here.

Contents

What Is Voluntary Discomfort?

Voluntary discomfort is precisely what it sounds like, to submit oneself to one or multiple forms of discomfort voluntarily.

Why on earth would anyone do that? For self-improvement, of course.

Voluntary discomfort is an ancient Stoic exercise that dates back to at least 2000 years ago when Seneca mentioned the practice in one of his Moral Letters to Lucilius.

“Set aside a certain number of days, during which you shall be content with the scantiest and cheapest fare, with course and rough dress, saying to yourself the while: ‘Is this the condition that I feared?” – Seneca

But before we discuss the many benefits of voluntary discomfort, let’s take a look at how you can participate in this Stoic exercise. There are two main forms of voluntary discomfort:

- Get Uncomfortable

- Forgo Pleasure

Some sources also include something in the likes of ‘temporary poverty,’ but that’s just a combination of getting uncomfortable and forgoing pleasure.

Get Uncomfortable

Getting uncomfortable, or as I like to call it, entering the belly of the beast, is quite simple. Just as the name suggests, it’s all about replacing the usual comforts with being uncomfortable.

Some examples of this form of voluntary discomfort include:

- Sleeping on the floor

- Taking Cold Showers

- Intermittent Fasting

- Not using the AC/Heater

- Eating only very basic meals

There are many ways you can participate in getting uncomfortable.

You can do any number of the things mentioned above for a couple of days. You can spontaneously decide to take a cold shower or sleep on the floor for the night. You can routinely get uncomfortable, such as sleeping on the floor once a week. You can even commit to one of these as a part of your lifestyle, such as intermittent fasting every day.

Spontaneously taking part in voluntary discomfort could be something as simple as not scratching an itch on your body.

It is up to you how you want to participate in getting uncomfortable, but the important thing is that once you’ve decided to do it, you should never back out. If you chose to sleep on the floor for the night, don’t get up in the middle of the night and get in bed; and certainly don’t allow yourself to make an excuse for quitting.

One way to help you combat the potential of quitting is to write it down before starting. For example, write it down somewhere that “I will not give up sleeping on the floor tonight no matter how uncomfortable it gets.”

Forgo Pleasure

At first glance, forgoing pleasure might seem easier than getting uncomfortable, but to truly forgo pleasure is indeed much more difficult than getting uncomfortable.

Here are some of the most often mentioned ways of forgoing pleasure:

- No drinking coffee or alcohol

- No eating dessert or snacking

Back in 40 AD in Rome, there are not nearly as many forms of pleasure and entertainment as we have today. Therefore, a modernized version of this exercise would be much more complicated.

Here are some examples of forgoing pleasure in the 21st century:

- No social media

- No streaming platforms, Youtube or TV

- No gaming

It’s easy to fast and endure the hunger when you can just distract yourself by going on an entertainment platform. It’s much harder when the forms of entertainment are removed.

These forms of entertainment are nothing more than distractions, whether from real-life problems or just as ways of killing time. They offer practically nothing of value to our lives and yet we are disproportionally spending more and more time on them.

Therefore, forgoing pleasure by eliminating forms of modern entertainment is perhaps the most effective form of voluntary discomfort.

Forgoing pleasure can also be spontaneous, but the best way to approach it would be to commit to it for a set number of days. For example, go three days without any forms of modern entertainment.

Just like getting uncomfortable, it’s easier to stick to it when you write down the rules before starting, for example, “I will not go on any forms of social media or streaming platform for three days.”

You can also combine forgoing pleasure and getting uncomfortable if you want to push your limits of discomfort and benefit even more from voluntary discomfort. I did this for three days and check out Part 2 for the main takeaways and lessons.

Voluntary Discomfort Benefits

As mentioned at the beginning of this post, the purpose of voluntary discomfort, just like all Stoic exercises, is self-improvement. Notably, the benefits include:

- Increased discipline

- Confidence Booster

- More Resilience

- Change of Priorities

- Self-Discovery

- Gratitude

Each of these six benefits in and of itself is a good enough reason to participate in Voluntary Discomfort, but all six combined really makes it worth it.

Increased Discipline

Discipline is like a muscle. It can be strengthened through usage and stress. Therefore, discipline is built by repeatedly making though choices; this is precisely how voluntary discomfort builds discipline.

When you are standing butt naked in the shower, facing the decision of whether to experience the uncomfortable cold shower or a nice and warm shower, it’s not easy to give up the comfortable for the uncomfortable.

By choosing the uncomfortable, your discipline is strengthened, the next time you are stuck between a comfortable choice vs an uncomfortable one, it will be easier to go with the latter.

If you are wondering why being able to choose the uncomfortable thing is important, here’s a quote for you:

“Discipline equals freedom.” – Jocko Willink

As contradictory as that sounds, it actually makes a lot of sense. Everything good in life comes at a cost, and that cost is usually hard work. In fact, most good things in life require one’s ability to choose delayed gratification over instant gratification.

Delayed gratification being something like working out every day to become fit, it requires discipline, takes a lot of hard work, and you don’t get to reap the benefits straight away, but it’s worth it in the long run.

Instant gratification would be to stay on the couch and enjoy a donut, it requires zero discipline, and you get rewarded straight away, but it does not improve your life in any way and is never worth it in the long run.

The quality of one’s life ultimately depends on how often they’re able to choose delayed gratification over instant gratification, and the more discipline you have, the easier it will be.

“Easy choices, hard life. Hard choices, easy life.” – Jerzy Gregorek

Confidence Booster

True confidence comes from within, more specifically, self-esteem. The more self-esteem you have, the more confident you are.

By voluntarily enduring the uncomfortable, you are not only increasing your discipline, but you’re also increasing your self-esteem.

Naturally, going through anything stressful or uncomfortable, especially willingly, will make you proud of yourself, and that in and of itself is enough to be a huge self-esteem booster sometimes.

A huge part of having confidence is also being comfortable with the uncomfortable. Voluntary discomfort does just that; it stretches and expands your comfort zone to make you more used to being uncomfortable.

Much like discipline, confidence is also an important part of life that is required in order to achieve certain things. Whether it’s public speaking, asking for a raise, or approaching an attractive stranger in a coffee shop, being confident is usually the barrier to entry of many things.

“You gain strength, courage and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, ‘I have lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.’ You must do the thing you think you cannot do.” – Eleanor Roosevelt

More Resilience

The second half of Eleanor Roosevelt’s quote perfectly encapsulates how voluntary discomfort can make you a more resilient person. “You are able to say to yourself, ‘I have lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.'”

Although I wouldn’t describe voluntary discomfort as a ‘horror,’ you get the point.

Resilience is also an important quality to have in life. All lives have their ups and downs; having resilience makes the downs much easier to endure.

Voluntary discomfort will make you realize that although it’s uncomfortable, it’s not at all terrible. You will realize that even if you were to be set back financially, you will be ok, because you’ve experienced sleeping on the floor, taking cold showers, and eating only the most basic meals.

Moreover, voluntary discomfort also builds your mental resilience as it trains you to become more comfortable with being outside of your comfort zone.

“You don’t develop courage by being happy in your relationships everyday. You develop it by surviving difficult times and challenging adversity.” – Epicurus

Voluntary discomfort is also somewhat stressful to endure, which builds your stress tolerance. If you think about it, for one to get used to a particular substance, the best and safest approach is to microdose. So in a sense, voluntary discomfort is kind of like microdosing stress.

To use another analogy, vaccines work by subjecting the person to a tiny amount of the virus so the immune system can learn to handle the virus and get used to killing it. Therefore, voluntary discomfort is kind of like a vaccine for stress, by subjecting yourself to a small amount of it, your body learns to get better at handling it.

Change of Priorities

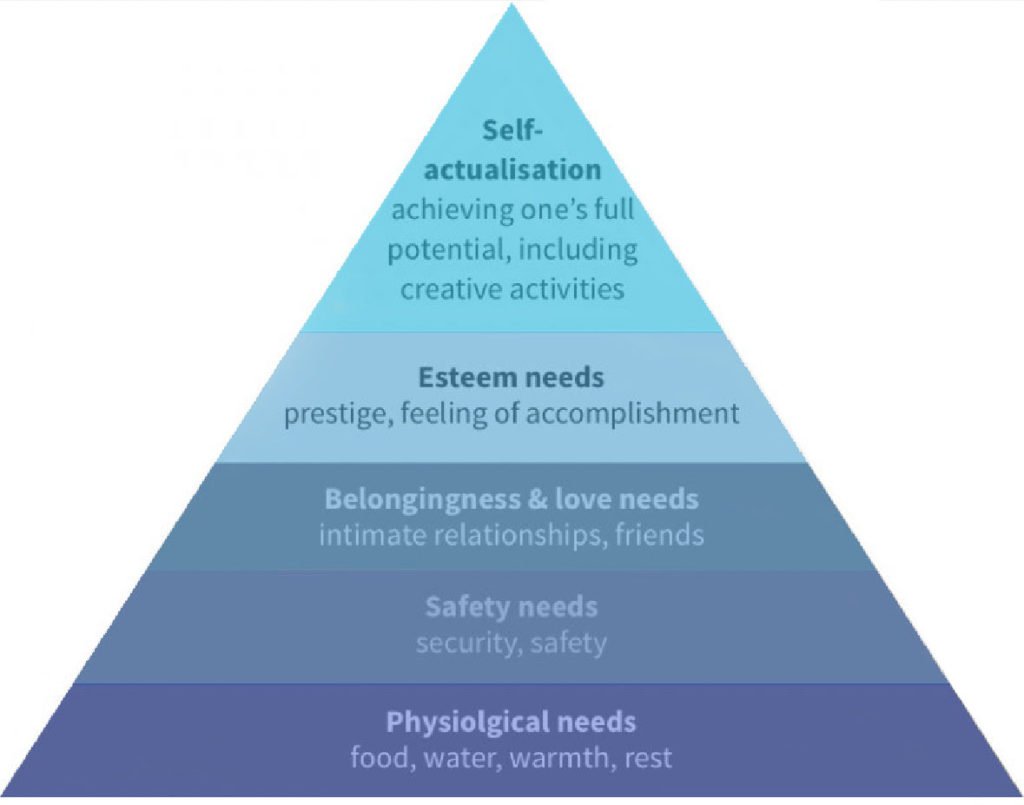

Voluntary discomfort can also give you a new perspective on life by subjecting you to the bottom levels of the hierarchy of needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

The hierarchy of needs works by levels of priority. For example, if you don’t have access to oxygen, you’re not going to care about being unemployed; if your safety is in danger, you’re not going to care about being respected by others.

If you do something such as fasting during your voluntary discomfort, you will be subject to quite a bit of hunger, and when that physiological need is not met, you are not going to pay attention to the other needs.

Therefore, as long as you remember what it was like to have your physiological needs in danger, you’re not going to care so much about the less important things in life, such as what others think of you.

When anyone goes through a near-death experience, they come out of it with a whole new perspective and stops caring about certain things in life that don’t provide any real value; their priorities change for the better. Voluntary discomfort achieves similar effects, but obviously on a lesser level compared to a near-death experience.

Self-discovery

“Man conquers the world by conquering himself.” – Zeno

By voluntarily subjecting yourself to discomfort, you learn more about yourself and how you handle these difficulties. In other words, you learn what you’re made of.

With this in mind, you can think about your newly discovered weaknesses and how they can be improved. The truth might be hard to swallow, but no harm can ever come from one learning more about oneself.

For example, if you learned that you find it extremely difficult not to check how many likes you got on social media, it could be a sign that you seek validation from social media. Once you know these problems exist, a simple google search can reveal how to fix most of these problems.

Gratitude

Often in life, it’s hard to be grateful for things that you don’t lack. This is where voluntary discomfort can help.

When you are taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor, you will think about how much you miss the warm water and a soft mattress. And once you go back to your comfortable lifestyle, you will have a newfound appreciation for the simple things in life. This sense of gratitude can significantly contribute to your happiness in life.

“Do not dream of possession of what you do not have; rather reflect on the grestest blessings in what you do have, and on their account remind yourself how much they would have been missed if they were not there.” – Marcus Aurelius

If you wish to learn more about other practical exercises in Stoicism, check out our free 7 Stoic Exercises Guide:

Related Posts:

What I Learned From 3 Days of Voluntary Discomfort

How to Be Invincible in Life – A Stoic Guide on Indifference

A Stoic Guide on How to Embrace a Crisis

[…] Voluntary discomfort can also be a great way to conquer desire. […]

[…] have a practice of voluntary discomfort, which is essentially an exercise in extreme lack of pleasure or comfort, in order to gain […]